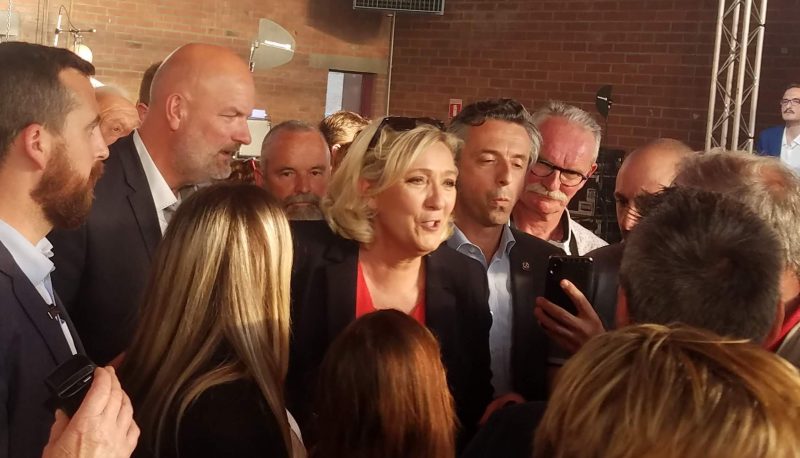

Two days before the European Union parliamentary elections, an auditorium in a scruffy coal town in the north of France filled with admirers of Marine Le Pen, friend of Vladimir Putin and Steve Bannon, and leader of France’s far-right Rassemblement National (RN) party. Her fortunes appeared to be running just about even with those of President Emmanuel Macron’s La République en Marche party. At least half of the crowd of 500 or so at the rally in Hénin-Beaumont, Le Pen’s home constituency, appeared to be well over the age of 50. A very loud band playing covers of American classic-rock songs rather poorly (their version of “Purple Rain” was particularly painful, if not flat-out ironic) signaled the baby-boomer character of Le Pen’s base, as did the massive coal pile visible from nearly every point in town. Hénin-Beaumont looks a bit like those hurting Pennsylvania towns that Trumplandia is said to comprise.

The band notwithstanding, the RN’s presentation was polished and forward-looking in terms of party-building. The two speakers who preceded Le Pen at the podium were young men; one of them, the 23-year-old Jordan Bardella, was tapped by Le Pen to top the list of candidates RN was putting forward for seats in the European Union parliament, from which she had favored France’s departure until the Brexit mess refused to end.

But now Le Pen had the opportunity to use her party’s long-standing fear-mongering tactics over the changing ethnic make-up of France to not only wound the neo-liberal Macron, but the whole of the multi-lateral European project and the reputation of regular, old liberal values themselves.

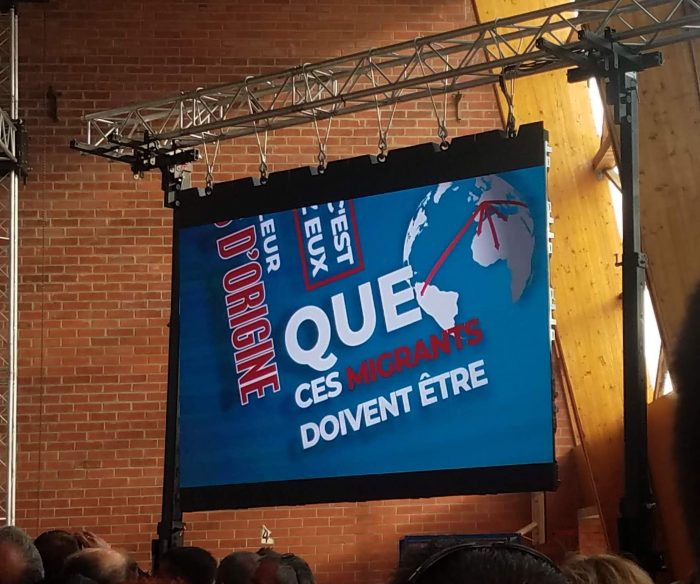

To the right of the stage, playing during the warm-up to the main event, was a large, high-definition screen displaying a seemingly endless loop of pictures of the photogenic Le Pen in various settings—with children and with local RN leaders. But then the loop stopped, along with the band, and the video panel filled with a series of animated text-and-graphics messages, accompanied by its own booming score.

As white and red text dropped onto the blue background, a graphic of the globe, turned so as to make Africa dominate and bring South America into the field of vision, appeared. The globe was marked with red arrows, meant to imply a horde of black and brown people breaching the cultural fortress of Europe.

“We believe that home for these migrants is in their home countries,” the text read.

There was no mistaking the relentless anti-migrant messaging of RN, or of the way in which Le Pen, with some success, painted Macron as the very symbol of an impending cultural death of all things French. Several days earlier, she told the audience at a rally in Burgundy that Macron “mustn’t come in first or he will abuse it to methodically deconstruct France,” as translated and reported by the Irish Times.

Moving from wine- to coal-country, Le Pen told her fans in Hénin-Beaumont that they were part of something big—an international uprising of the little people against the global elites. There, to the cheers of those assembled, Le Pen defined the May 26 vote as an existential battle for France, Europe, and civilization as a whole, and that the way to save the nation, the continent and civilization itself was to vote for RN candidates as a way of “saying ‘no’ to Macron’s destructive vision for Europe.” There were more cheers, as rally-goers waved French flags.“ Speaking of the far-right parties of other EU member states, Le Pen invoked a catch-phrase frequently heard on the right: that of “a Europe of nations,” which is defined in opposition to the very notion of an EU with the power to issue regulations on all the member states. “With our European allies who also embody the awakening of peoples, for the first time in 60 years, we have the opportunity to initiate … the construction of a Europe of nations, and to end this European Union.” In other words, start dismantling the bureaucracy from within or, at the very least, seat enough far-right members of the European parliament to gum up the works.

That part about the “awakening of peoples”? That’s Le Pen’s reference to the rise of far-right parties in countries throughout Europe, from Italy to the U.K., and from Hungary to Spain. And if that phrase “a Europe of nations” is beginning to sound familiar to you, it’s because none other than Steve Bannon, the self-appointed guru to, and gatherer of, far-right figures across the globe, has taken it up. As the election campaign entered its last week, Bannon stories flooded the media as the banished one-time White House operative received a steady stream of reporters at a suite in the Hotel Bristol, a five-star property in Paris where Bannon was said to have paid $6,000 a night for his digs.

As election results began to come in on Sunday night, it was clear that Le Pen’s party bested Macron’s by a couple of seats—winning nearly 24 percent of France’s total vote. Although those results are not much different than what Le Pen’s party (then called the Front National) gleaned in the 2014 EU elections, the symbolic defeat of Macron was huge, cast as a clash of worldviews.

Nonetheless, the road to that victory was a bit bumpy. Le Pen’s ties to Putin returned to the spotlight, especially a mysterious loan her party received in 2014 from a Russian bank that then went under. Then there was that irksome selfie she posed for with Ruuben Kaalep, a member of Estonia’s parliament who has links to neo-Nazis. Kaalep photographed the two making a “white power” sign with their hands—a gesture that mimics an “OK” sign that was once used as a way to troll liberals, but after enough repetition was adopted at face value by some far-right types as a kind of not-so-secret handshake.

The selfie, posted by Kaalep to his Facebook page, caused enough of a stir that even The New York Times ran a story about the photo and the blowback the French leader received for it. Le Pen pleaded ignorance of the gesture’s meaning, saying that Kaalep asked her to make it, and she complied. However, there has been ample news coverage of Kaalep’s white supremacist leanings, and there she was, hanging out with him.

It seems that a lot of far-right types in Europe are hanging out with each other these days. It was Bannon’s dream to bring them all together so that they might form a voting bloc within the EU Parliament that could gum up the works. And while Bannon’s scheme, dubbed The Movement, never really got off the ground as a Bannon-branded project, Italy’s Matteo Salvini, that country’s interior minister and leader of the far-right La Liga party, stepped in to convene a multi-national, multi-party far-right rally in Milan. That placed some of the most bigoted and reactionary political figures in all of Europe on one stage—and drew thousands of supporters to the plaza where the event took place.

Salvini, however, wasn’t able to wrangle all of Europe’s far-right authoritarians. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, whose far-right Fidesz party ultimately won a landslide in the EU elections, apparently couldn’t see fit to hang with the small-fry whose parties have yet to rise to ruling status. Jaroslaw Kaczynski, who leads Poland’s ruling far-right Law and Justice Party, has issues with the many Russia-facing right-wing leaders in Salvini’s coalition and was not present. And Nigel Farage was too busy selling his insta-party (just add money and stir up the populace), simply called the Brexit party, to the electorate to show up. Since the elections, Salvini has so far failed to woo Orbán, who just declined the Italian leader’s invitation to join the bloc of far-right parties he is building within the European Union.

The photos from Salvini’s May 19 Milan gathering show a cheerful Le Pen, who was about to confront another problem. Her pal, Steve Bannon, air-dropped himself onto her turf just days ahead of the election to promote himself as the Man with the Plan at just the moment when it was not to a nationalist leader’s advantage to have an American materialize presenting himself in a way that suggested he’d had something to do with her success—which he very may well have had.

One thing’s for certain, Europe’s far right seems to have a lot of money to spend, and nobody seems to be able to say where it’s coming from. Le Pen herself has said she turns to Bannon for fundraising advice. When she rebranded her party a year ago under its new name (in order to distance it, at least in public view, from the anti-Semitism and Holocaust denialism that its earlier Front National was known for), Bannon was on hand for the roll-out at the party’s national convention, where he told party members to wear the term “racist” like “a badge of honor.” But when the guru of the dark forces turned up in the City of Lights as the EU election campaign was reaching its peak, Le Pen insisted Bannon had “no role” in her party’s campaign, even though two of her deputies made a pilgrimage to the Bristol to pay a call on the big guy.

Pro-democracy observers of the EU’s parliamentary elections found bright spots to tout: Turnout overall is up significantly, and even as the right grabbed its biggest slice of the multinational legislative body yet, so did the Greens. But that sort of analysis ignores the fact that the right is on the rise, and that in three major EU countries—U.K., France, and Italy—far-right parties are emerging as their nation’s largest parties, at least in terms of their presence in the EU, an organization they would love to kill.

As Cas Mudde wrote at The Guardian:

Rather than a victory for democracy, the European elections, and the responses to the results, show how much populism in general, and the populist radical right in particular, has become mainstreamed and normalised. We find it normal that a neo-Nazi party is the third biggest party in a member state, that a populist radical right wins more than half of the vote in non-democratic elections, and that the populist radical right is the biggest party in several EU member states. We celebrate that “the majority has voted for pro-European parties”. We ignore that turnout in one in five member states was (well) below one-third of eligible voters.

Indeed, one of the most troubling aspects of Le Pen’s rally in Hénin-Beaumont was just how perfectly normal it all seemed. Nowhere did one feel the kind of ready-to-explode energy of a Trump rally, or a gathering of Germany’s far-right Alternatives für Deutschland party. Just nice, middle-class people expressing their contempt for people who don’t look like them—and then charmingly singing the Marseillaise in unison before calling the event to a close.

After the rally concluded, a white-haired attendee in a pink skirt-suit was seen walking to her car. Emblazoned on the back of her jacket in black letters were the words, “LOVE ROCKS.”

Adele M. Stan explored the European Union parliamentary elections as a guest of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, an independent foundation affiliated with Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD).