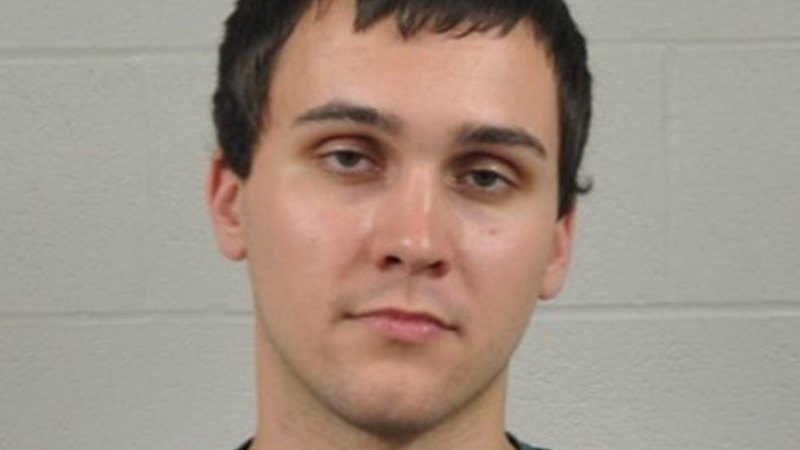

A circuit court judge for the state of Maryland ruled on Wednesday that prosecutors can present a jury with evidence that Sean Urbanski, a white college student charged in the stabbing death of a black college student, had racist photographs and memes on his phone, and had liked an “Alt Reich: Nation” Facebook page.

The May 2017 stabbing of Richard Collins, a soon-to-be graduating Bowie State University student, was witnessed by two people who had been standing with Collins when he was assaulted, and was captured on video by a bus stop security camera.

Urbanski’s trial is set to begin on July 22; Wednesday’s hearing was about motions by defense attorneys to dismiss the hate crimes charges as a violation of the First Amendment, and to suppress the digital evidence as irrelevant to the crime and so inflammatory that it would make it impossible for Urbanski to get a fair hearing from a jury. Defense attorneys also sought to separate any prosecution of Urbanski’s alleged hate crimes from his trial for Collins’ murder.

In today’s proceedings, the motion to suppress the digital evidence was the focus of arguments by prosecutors and defense attorneys, and questions from Circuit Court Judge Lawrence Hill Jr.

Urbanski’s lawyers acknowledged that memes on his phone at the time of the killing were “stupid” and “offensive,” but said that possessing racially insensitive material is not illegal, and that there was no connection between the images and the killing. They insisted that according to Maryland case law, generalized evidence of racial prejudice is not sufficient on its own; evidence must have some kind of direct “nexus” to the crime.

Prosecutors insisted that the photographs, saved in the “images” folder of Urbanski’s cell phone, were especially relevant to the case given video evidence that Urbanski had walked past a white man and an Asian woman before stabbing Collins in the chest. Defense attorneys argued that the video does not prove a racist motive, because the other two people responded to the “out-of-his-mind drunk” Urbanski’s shouted demands to step out of his way while Collins stood his ground.

In the courtroom, a large screen television was wheeled in so that prosecutors could walk the judge through the security camera video and the digital files extracted from Urbanski’s phone. The video screen was turned toward the judge so that people sitting in the courtroom, including Collins’ family members, could not see the images. But lawyers described the crime video in explicit detail.

To make their case for the relevance of the phone images, prosecutors showed the judge the memes in question—calling them “photographs”—that had been saved on specific dates in December 2016 and in January, February, and April 2017, leading up to the month of the killing. One image included a noose and a handgun; others, they said, advocated violence against black people.

In announcing his ruling, the judge described some of the images on the phone as racist jokes, but said that other images demonstrated violence. It should be left to a jury, he said, to weigh the evidence and hear the arguments about the relevance of the images to the question of Urbanski’s intent on the night of the killing.

One question raised by the judge that neither side’s attorneys could answer definitively, which presumably will be addressed by a technical expert at the trial, was whether Urbanski would have had to take proactive steps to save the memes in his “images” folder or whether they might appear there if he simply opened an email or text containing them. Prosecuting attorneys noted that the images were included amid photos of his girlfriend, student events, and other such material. They said courts have recognized that the intimate data on someone’s cell phone says a lot about them. The images on Urbanski’s phone, they argued, “are about who he is and what he is about.”

The attorneys did not spend much time addressing the subject of the “Alt-Reich” Facebook page mentioned in court documents. When the judge asked about it, defense attorneys read from a 2017 New York Times article in which the page’s founders disavowed white supremacy and described the page as an intentionally offensive effort to be funny.

In 2017, University of Maryland Police Chief David Mitchell said of the Facebook page, “When I look at the information that’s contained on that website, suffice it to say that it’s despicable, it shows extreme bias against women, Latinos, persons of Jewish faith and especially African Americans.”

As Jared Holt of Right Wing Watch and Luke Barnes of ThinkProgress have noted, some online advocates of white nationalism or identitarianism “hide their racism and anti-Semitism behind layers of ‘irony’ and ‘humor.’” Alice Marwick, co-author of a Data & Society Institute report on online disinformation, told the Guardian’s Jason Wilson, “Irony has a strategic function. It allows people to disclaim commitment to far-right ideas while still espousing them.”