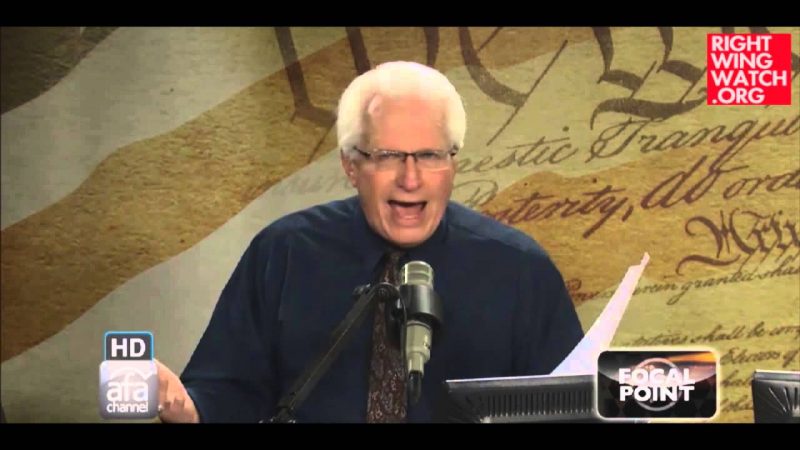

Bryan Fischer spent the entire first hour of his radio program today discussing the passage of marriage equality legislation in New York last week in typical Fischer-fashion … which means me focused on warning about the health risks of gay sex while railing against the “hate crimes” gay activists are committing against Christians.

And, for good measure, he also explained that there was no need to “marriage equality” legislation because gays already have the equality to marry … anyone of the opposite sex:

Allow me to just point out, once again, that this is literally the same argument made in defense of anti-miscegenation laws:

When societies decide who can and who can’t legally marry, they determine who is and isn’t really a part of the family. These inclusions and exclusions take place at such an intimate level that they shape what seems natural and, in turn, what is stigmatized as unnatural.

…

From the 1860s through the 1960s, the American legal system elevated the notion that interracial marriage was unnatural to commonsense status and made it the law of the land. During this period, miscegenation law channeled property, propriety, personal choice, and legitimate procreation into one very particular kind of monogamous marital pair: couples that were made of up one White man and one White woman, whose sameness of race was required by law and whose difference in sex was taken entirely for granted. The more Whites believe that interracial marriage was unnatural, the more they assumed that the marriage of one White man to one White woman was the only kind of marriage worthy of the name – and the more they saw their own marriages as the fortunate result of individual romantic preference rather than the obligatory outcome of a legal system steeped in gendered assumptions about race and heterosexuality.

…

The constitutional fiction of miscegenation law held that laws punishing both partners in an interracial relationship were racially equal rather than racially discriminatory. This, for example, was the position the Alabama Supreme Court put forth in 1881 in Pace v. State, a case involving a White woman and a Black man, when it ruled:

The fact that a different punishment is affixed to the offense of adultery when committed between a negro and a white person, and when committed between two white people or two negroes, does not constitute a discrimination against or in favor of either race. The discrimination is not directed against the person of any particular color or race, but against the offense, the nature of which is determined by the opposite color of the cohabiting parties. The punishment of each offending party, white or black, is precisely the same. There is obviously no difference or discrimination in the punishment. The evil tendency of the crime of living in adultery or fornication is greater when it is committed between persons of the two races than between persons of the same race.

The was also the position the Oregon Supreme Court maintained a half century later when it ruled that its miscegenation law did not discriminate against Indians because it “applies alike to all persons, either white, negroes, Chinese, Kanaka, or Indians.”