The Religious Right’s mixed reaction to last week’s highly staged Rose Garden signing of an executive order on religious liberty might be a useful gauge of leaders’ level of cynicism—or their willingness to play along with Trump’s own cynical use of religion, like his Bible-waving on the campaign trail.

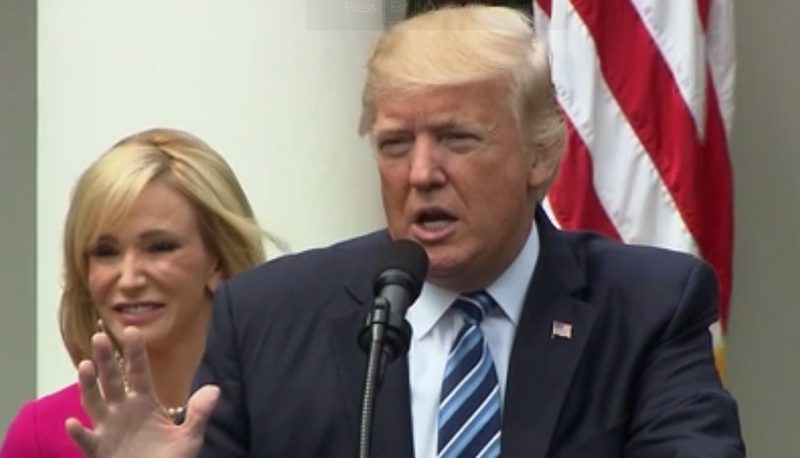

President Trump gathered many of his Religious Right backers for a Wednesday evening dinner, and then on Thursday held a photo-op in the White House Rose Garden where he could get pictures taken with individuals like Cardinal Wuerl, archbishop of Washington, D.C., Rabbi Marvin Hier, who prayed at his inauguration, and Penny Nance of Concerned Women for America.

Trump’s rhetoric about protecting religious liberty was soaring, but the actual language of his order fell far short, so much so that the American Civil Liberties Union, which had geared up to challenge the order in Court, announced that it wouldn’t bother because “it turned out the order signing was an elaborate photo-op with no discernible policy outcome.”

Trump elevated the issue of the Johnson Amendment throughout his presidential campaign, warning that it was used to bully and censor pastors by threatening to take away their tax-exempt status if they engage in explicit electoral politics, even though, as Dahlia Lithwick notes, the “only such instance anyone can cite is a 1995 case in which the IRS denied the nonprofit status of an upstate New York church after it took out a full-page newspaper ad warning Christians not to vote for Bill Clinton.”

Rather than address the politically charged question of whether business owners, among others, can use their religious beliefs to justify refusal to provide services to LGBTQ people or same-sex couples, Trump’s order took a tepid step toward fulfilling his campaign promise to “destroy” the Johnson Amendment, the legal restriction that bars churches and other tax-exempt nonprofits from engaging directly in electoral politics. Conservative Christian writer Rod Dreher complained that the executive order contains “nothing—zip, nada—to protect the religious liberty of people who dissent from LGBT rights dogmas.”

Trump was eager for a photo-op with the Little Sisters of the Poor, who have been arguing in court that the Obama administration’s accommodation for religious groups opposed to contraception being covered in their employees’ insurance policies did not go far enough. But even in their case, all Trump’s order does is direct the Treasury, Labor and HHS departments to “consider” changing their regulations.

Reaction by Religious Right leaders seemed to depend in part on whether a person had been an eager Trump booster or more on the skeptical-to-Never-Trump end of the spectrum. Many who had hoped for an order similar to the sweeping draft that leaked three months ago were bitterly disappointed. Radio host Steve Deace called the executive order “the definition of getting peed on and being told it’s raining.” Deace had harsh words for Trump’s cheerleaders: “Believers should pay very close attention to who shills for this fake religious freedom executive order, and who tells the truth.”

He had plenty of company. “Religious conservatives, we’ve been had,” said Dreher. “Who can plausibly deny it now?” Robert George, a Princeton University professor and the leading intellectual of the anti-LGBTQ Right, fumed that Trump was getting cheered for “nothing,” calling the order “meaningless” and a “betrayal.” Writer Mark Silk called it a “nothingburger” that is “the presidential equivalent of stamping your feet in the Sahara to keep away the elephants.”

Saying that the “bull market for cynicism about Donald Trump continues,” Dreher wrote caustically, “If you are a preacher eager to politicize your pulpit and make yourself useful to Washington power brokers, President Trump is on your side.” Dreher is among religious figures across the political and religious spectrum who support the Johnson Amendment because they believe it protects the church from political manipulation. “The only thing of substance in this thing,” he wrote, “is that the president wants to free preachers up to raise money for him from the pulpit.”

The Heritage Foundation’s Ryan Anderson, a leading opponent of marriage equality and LGBTQ nondiscrimination laws, was dismissive of the “woefully inadequate” order, which he said was “a mere shadow of the original draft leaked in February.”

Twice now, he has failed to stand up for commonsense policy on religious liberty when liberal opponents lashed out against it.

Back in February, he caved to the protests of liberal special interest groups as he declined to issue an executive order on religious liberty that had been leaked to hostile press.

NOM’s Brian Brown similarly said Trump failed to deliver on his promises, saying he “punted” the issue to the Justice Department:

This is the second time that President Trump has backed away from signing a comprehensive order protecting religious liberty after LGBT groups complained about the proposed actions. We cannot accept this capitulation on such a critical issue and must fight back.

In the National Review, David French called the order “a sop to the gullible.” Alliance Defending Freedom’s Gregory Baylor called it “disappointingly vague.” ADF President Mike Ferris said the “spirit” of the order provided some hope, but its content was a “gesture” that left his campaign promises unfulfilled.

Those who have been Trump’s biggest cheerleaders were far more charitable. At the dinner on Wednesday evening, Dallas preacher Robert Jeffress told Trump, “We’re going to be your most loyal friends. We’re going to be your enthusiastic supporters. And we thank God every day that you’re the president of the United States.” Franklin Graham was also in the house; he said the order is evidence that Trump delivers on his campaign promises, saying, “80 percent is better than nothing.” Jerry Falwell, Jr. declared Trump has been evangelicals’ “dream president.”

The Rose Garden ceremony was kicked off by prosperity gospel preacher Paula White, considered the closest thing Trump has to a spiritual adviser. Among those in the audience were anti-gay activist Jim Garlow and “prophet” Cindy Jacobs.

Garlow noted on his Facebook page about the “God-fearing, Bible-believing people” criticizing the executive order for not going far enough. He called the order “a remarkable first step” and he said that the people who joined Trump for dinner and the signing ceremony were praising God for it. “Admittedly we need to be vigilant to see follow up steps,” he wrote, “but this was a great moment for (1) the US Constitution, (2) people of biblical values, (3) people of any faith and (4) the future of the Republic.”

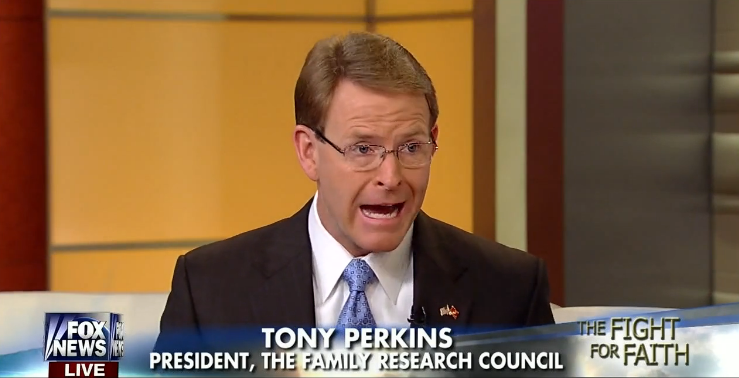

Family Research Council’s Tony Perkins praised Trump’s order as “a clear reflection of his campaign promise to protect the religious freedoms of Americans.” He said it “starts the process of reversing the devastating trend set by the last administration to punish charities, pastors, family owned businesses and honest, hard-working people simply for living according to their faith.” Added Perkins, “The open season on Christians and other people of faith is coming to a close in America and we look forward to assisting the Trump administration in fully restoring America’s First Freedom,” said Perkins.

Political operative Ralph Reed gushed that the order “removes a sword of Damocles that has hung over the faith community” and “lifts a cloud of fear over people of faith and ensures they will no longer be subjected to litigation, harassment and persecution simply for expressing their religious beliefs.” He made clear that he’s also looking for more, calling the order “the first bite at the apple, not the last.”

At Slate, legal writer Dahlia Lithwick and People For the American Way Senior Fellow Elliot Mincberg took a look at legal phrases inserted into the order which strip it of much of its potential power, suggesting that those changes may have been made by White House lawyers to help the order survive a legal challenge. Citing the gulf between Trump’s sweeping rhetoric and the stunted order, they ask, “Did Trump know that the executive order would achieve none of the things he had promised on the stump or at the signing ceremony? Or did nobody bother to tell him?”

At Think Progress, Ian Millhiser notes that the order includes provisions that could lead to serious problems down the line, once agencies decide to take action. He notes that the order asks Attorney General Jeff Sessions—described by Millhiser as “an anti-LGBTQ former senator who was denied a federal judgeship due to the Senate Judiciary Committee’s concerns that he is racist”—to “issue guidance interpreting religious liberty protections in Federal law.”

And, of course, even before signing the executive order, Trump had already done quite a bit to pay back Religious Right leaders for their electoral support, including his nomination of far-right judge Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, his attacks on Planned Parenthood and women’s access to contraception around the world, and his appointments of anti-choice and anti-gay extremists to high-level executive branch positions.