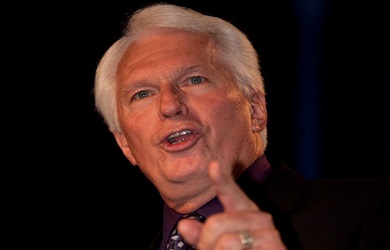

Last week we told you about an excellent profile of Bryan Fischer in the New Yorker and Fischer’s predictably over-the-top and inaccurate attacks on the article and author, Jane Mayer. In the wake of those attacks, Mayer has posted a follow-up blog post, “Have Not Love: How Bryan Fischer Turned on a Friend,” that sets the record straight and explores the twisted family values of Fischer, a so-called family values advocate:

As I worked on my profile of the influential conservative radio-host Bryan Fischer, I was struck by the difference between the “pro-family” values he espouses and some of the choices he has made in his own life. For example, Fischer has not seen his only sibling in something like a decade—a sister with serious health problems who lives on social security and welfare disability payments. Perhaps more revealing, though, is the broken friendship between Fischer and another conservative Christian activist, Dennis Mansfield.After the article came out, Fischer accused me of misrepresenting an anecdote concerning his relationship with Mansfield. Since then, Mansfield has weighed in on his own blog to defend the accuracy of the New Yorker story, and expanded on what he calls Fischer’s “divisive” politics as a dead end for this country.

Mansfield, who unsuccessfully ran for Congress, parted ways with Fischer after his son was arrested for drug possession:

The public arrest torpedoed Mansfield’s congressional bid. More importantly, he says, the episode, and the subsequent humility he learned from his son’s struggle, caused him to reëxamine the way in which he was using his Christian faith as a cudgel in politics. As Mansfield told me, he concluded that “faith-based conservatives are either purposefully or inadvertently looking punitively at other people” rather than “lifting each other up.”While Mansfield’s family crisis caused him to reassess his earlier self-righteousness, Fischer, he says, reacted to it heartlessly, and told Mansfield that he was no longer fit to be an elder at the church where Fischer was preaching, the Community Church of the Valley, in Boise, Idaho.

Writing on his blog last Thursday, Mansfield said this about Fischer:

Pushing your own agenda using the veil of religion has been used all throughout history. Today is no exception, and individuals in the evangelical community do it as much as anyone else. When someone wraps their own hate speech in a “god blanket” it makes it easier for a subset of people to accept, and eventually it may even gather a following. The problem is that anyone outside of that subset is turned away from not only that particular subset, but from the entire religion.

Mayer sees echoes in the generational divide within the evangelical community of Fischer and Mansfield’s opposing outlooks:

The contrast between Mansfield’s message and Fischer’s in some ways captures a larger split within the evangelical Christian movement, concerning how much tolerance to show towards those who in the past may have been treated as outliers, including homosexuals. Polls of younger evangelicals, like those of younger voters of almost all stripes, show growing acceptance of gay rights, including same-sex marriage. Times, and attitudes, are changing.

Let’s hope she’s right about the younger generation being more like Mansfield than Fischer.