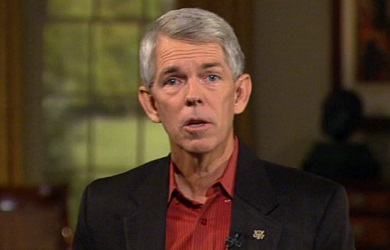

Towards the very end of the televised portion of David Barton’s interview on The Daily Show, Barton said that one of the cases he “did at the US Supreme Court was rabbi Leslie Gutterman was asked in Providence Rhode Island to give a prayer at a graduation, and he wasn’t allowed to, now tell me how “Congress should make no law’ means that a rabbi cant say the word ‘God’ at a prayer.” He claims that this poses that the first Amendment is misused by putting a restriction on individuals, rather than government.

He referred to the case of a Rhode Island rabbi who was invited to deliver a prayer at a public school graduation to demonstrate that the Constitution is being misapplied to stifle religious expression. But it was the public school, not the rabbi (Gutterman), that was the defendant in the Supreme Court case Lee v. Weisman. Robert Lee was the principal of the school who invited the rabbi and Daniel Weisman’s daughter was the graduating student at the school who objected to the prayer service.

In the following section, that was posted only online, Barton dismisses fears that people could be coerced into prayer in schools, saying, “there’s coercion, you have to pull on your big boy pants and do something” and “look at all the pressure that goes to school anyway, there’s drugs and everything else and we don’t rule that unconstitutional.”

Barton misconstrues the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which is incorporated to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment (see Everson and Cantwell), and calls the ruling a “pretty strange parsing of the Constitution” and places a “restriction on the rights of people to say the word God in public.”

As Justice Kennedy writes in the majority opinion, which decided that the school is barred from holding a prayer service during the graduation ceremony, the First Amendment has been interpreted to prevent the government from sanctioning or endorsing religion:

The First Amendment’s Religion Clauses mean that religious beliefs and religious expression are too precious to be either proscribed or prescribed by the State. The design of the Constitution is that preservation and transmission of religious beliefs and worship is a responsibility and a choice committed to the private sphere, which itself is promised freedom to pursue that mission. It must not be forgotten, then, that, while concern must be given to define the protection granted to an objector or a dissenting nonbeliever, these same Clauses exist to protect religion from government interference.

As Stewart notes, Barton completely neglects the rights of the students whose beliefs are compromised by the school-sanctioned prayer by putting the burden on the student to just put up with it. Kennedy writes that such thinking “turns conventional First Amendment analysis on its head. It is a tenet of the First Amendment that the State cannot require one of its citizens to forfeit his or her rights and benefits as the price of resisting conformance to state-sponsored religious practice.”

Barton grounds his beliefs that the majority should trump the rights of the minority in his view that the First Amendment actually doesn’t prevent the state from endorsing religion. Lauri Lebo writes in The Devil in Dover that in Barton’s book The Myth of Separation,

Barton argues in his book that the First Amendment only refers to the establishment of a specific Protestant denomination. In other words, Barton claims that Christian founders were saying they couldn’t endorse Lutheranism, for instance, over Presbyterianism. But in Barton’s view, forcing Christian beliefs on the nation’s citizens has always been fair game.

But the drafters actually rejected proposed amendments that only stopped governmental recognition of denominations or sects. Warren Throckmorton, a professor at Grove City College, a Christian school, pointed to James Madison’s speech during the debate over the First Amendment where he makes clear that “Congress should not establish a religion, and enforce the legal observation of it by law” for otherwise they could pass laws that “might infringe the rights of conscience and establish a national religion.”

By ignoring the meaning behind the First Amendment and opposing the First Amendment’s incorporation to the states under the Fourteenth Amendment, Barton pushes a radical version of the Constitution. If “taken to logical conclusion,” Throckmorton notes, “this argument would establish Christianity as the religion of the nation, something the Founders specifically did not do.”