David Barton has been actively promoting his soon-to-be-released book, The Jefferson Lies, and one of Barton’s central claims is that Jefferson actually wanted to use “The Jefferson Bible” to evangelize Native Americans. Craig Ferhman in the Los Angeles Times yesterday discussed the Jefferson Bible and dissected Barton’s erroneous assertions, writing that Barton “cherry-picked” and “distorted” Jefferson’s work in order to make it “fit the Religious Right’s agenda.” Barton has a long track record of misrepresenting history to make it seem that Jefferson was trying to proselytize the Native Americans, and Ferhman says that the right-wing pseudo-historian even used an “outrageous fabrication” while arguing that Jefferson gave “The Jefferson Bible” to missionaries.

Ferhman also details how many of Jefferson’s opponents tried to stoke fears that he was an enemy of Christianity and that “some families buried their Bibles in their gardens” following his election as President. Much like today when Republican and conservative leaders say Obama is leading a “war on religion” and is “hostile toward Christianity,” many of Jefferson’s adversaries warned that a vote for Jefferson was “no less than rebellion against God” and a “sin against God,” dubbing him an “an open enemy to their religion, their Redeemer.” Barton himself consistently stokes fears about Obama and his religious faith, telling voters that God will hold those accountable who don’t vote the way Barton would like them to.

Ferhman appropriately writes that “Barton loves to cherry-pick a phrase and manipulate it support his side in a partisan, present-day debate,” and notes that presidential candidates like Newt Gingrich and Rick Perry continue to give Barton unmerited praise:

In a presidential campaign, and in the hands of Jefferson’s enemies, this passage became proof of the candidate’s radicalism. One popular pamphlet from a pro-Adams minister quoted “Notes,” then countered it: “Let my neighbor once persuade himself that there is no God,” the minister warned, “and he will soon pick my pocket, and break not only my leg but my neck.”

Such attacks proved effective enough that, when Jefferson did win the election, some families buried their Bibles in their gardens, fearing the new president would burn them. So it made sense that Jefferson continued to keep his religious views private. Years later, after he and Adams had resumed a correspondence, Jefferson described Jesus’ teachings as “the most sublime and benevolent code of morals.” The problem, he wrote in another letter to Adams, came in the “artificial scaffolding” that surrounded those teachings — the Virgin Birth, the miracles and so on.

“The Jefferson Bible” is his attempt to tear down that scaffolding. Jefferson took his first stab at it while still president. In the White House, “after getting through the evening task of reading the letters and papers of the day,” he used a razor to slice Jesus’ teachings out of a couple of King James Bibles, then grouped them by subject (e.g., “false teachers”) and pasted them into a scrapbook. Its title page included these words: “an abridgment … for the use of the Indians.” Scholars agree it was most likely a sly joke about the impossibility of circulating such a genuinely radical book, or perhaps a joke about Adams’ political allies, whom Jefferson referred to as “Indians” in his second inaugural.

…

Today, the facts about “The Jefferson Bible” might seem like an impossible obstacle to anyone who wants to fashion Jefferson as a hero for right-leaning Christians — and America as a “Christian nation.” Instead, the book has been distorted to fit the religious right’s agenda.

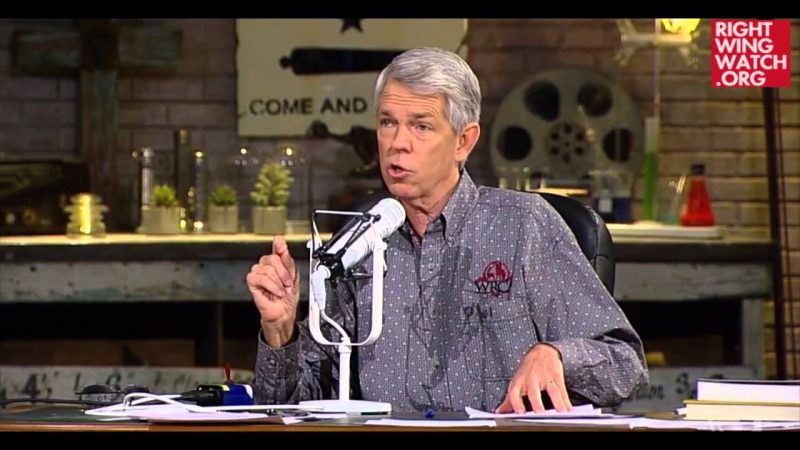

There’s no better example of this than David Barton, an amateur historian who’s become quite popular with Perry, Santorum and Michele Bachmann. Barton loves archival flourishes — his Texas offices include a concrete vault filled with 18th century arcana — but his true concerns lie in the present. Though Barton admits that “The Jefferson Bible” often comes up as proof that its namesake wasn’t the evangelical Christian conservatives want him to be, he also says he can refute this. In a TV appearance in 2010, Barton fixated on Jefferson’s “Indians” title page, mixed in some unrelated material about Jefferson’s Indian policy, then pivoted to an outrageous fabrication: “He then gave it to a missionary,” Barton said of Jefferson and his Bible, “and he said, ‘Here, if you get this printed, and you use this as you evangelize the Indians.'”

There’s absolutely no evidence of Jefferson giving either version of his Bible to anyone other than his bookbinder. Perhaps it’s no surprise that last year, in Iowa, Newt Gingrich said, “I never listen to David Barton without learning a whole lot of new things.” That’s because Barton loves to cherry-pick a phrase and manipulate it support his side in a partisan, present-day debate.

But there’s a bigger problem with Barton’s method: He strips history of its complex human appeal. After all, “The Jefferson Bible” stands as one of the most interesting and iconoclastic moments in America’s religious past — one man with a razor, a pot of paste and a unique and private set of ideas. They were intricate ideas: Jefferson was no more a Bible thumper than he was a Bible burner. And that’s why he and his handmade book have enjoyed such an odd and exciting afterlife. After one politician got his 14 copies of the 1904 edition, he reported receiving more than 2,000 requests from his constituents.