President-elect Donald Trump’s announcement that he will nominate Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama to be attorney general has revived interest in the first time Sessions appeared before the Senate for confirmation: in 1986, when the Republican-led Judiciary Committee rejected his nomination to a federal judgeship thanks to alleged racist comments he had made and the fact that he had used his power as a federal prosecutor to go after civil rights activists registering African Americans to vote.

Much of the 500-plus page transcript of Sessions’ 1986 confirmation hearings consists of his denials or attempted explanations of various alleged racist comments, such as calling an African-American attorney “boy” and “joking” that he only disapproved of the KKK after he learned that they smoked marijuana.

But one passage of the transcript, a conversation with Democratic Sen. Paul Simon of Illinois and Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts, reveals how Sessions approached the issue of civil rights and how he could insist that he was a supporter of civil rights while having the record that he did.

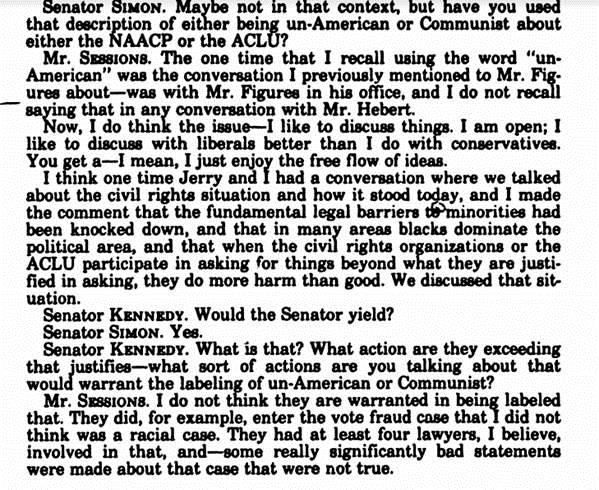

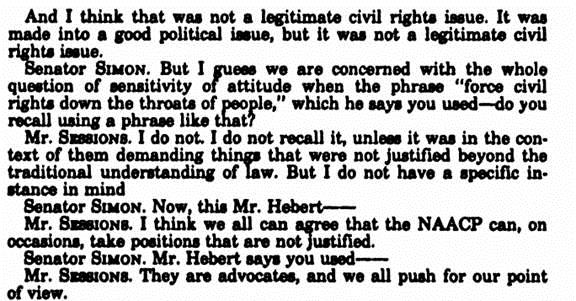

Simon pressed Sessions on allegations that he had called the NAACP and the ACLU “un-American” and “communist”—which Sessions had previously said could have been a reference to foreign policy positions by the groups that could have been perceived as “un-American” by others—and that he had said those groups “force civil rights down the throats of people.”

Sessions told Simon that at one point he had had a conversation with then-Justice Department attorney Gerald Herbert “where we talked about the civil rights situation and how it stood today, and I made the comment that the fundamental legal barriers to minorities had been knocked down, and that in many areas blacks dominate the political area, and that when the civil rights organizations or the ACLU participate in asking for things beyond what they are justified in asking, they do more harm than good.”

When Kennedy asked him for an example of such overreach by civil rights groups, Sessions cited the NAACP’s involvement in a “vote fraud” case that he “did not think was a racial case” and “was not a legitimate civil rights issue”:

Although it’s not entirely clear in context what “vote fraud” case Sessions was referring to, it is presumably the case that became a focal point of his confirmation hearings. The Nation’s Ari Berman describes it:

On March 7, 1965, Albert Turner, a tall, sturdy bricklayer from Marion, Alabama, walked directly behind John Lewis during the infamous Bloody Sunday march in Selma. When Lewis fell from the force of police blows, so did Turner. “I fell down and ran,” he said. “Then I fell down again and ran some more.”

After the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), Turner became known as “Mr. Voter Registration,” working as Alabama field secretary for Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. After King’s assassination, Turner led the mule wagon that carried King’s body through the streets of Atlanta.

Because of Turner’s work, African-Americans gained political control of many counties in the Alabama Black Belt, where you could practically count the number of black voters on one hand in 1965. But the flourishing of black political power in the Black Belt didn’t sit well with the old white power structure.

In the Democratic primary of September 1984, FBI agents hid behind the bushes of the Perry County post office, waiting for Turner and fellow activist Spencer Hogue to mail 500 absentee ballots on behalf of elderly black voters. When Turner and Hogue left, the feds seized the envelopes from the mail slots. Twenty elderly black voters from Perry County were bused three hours to Mobile, where they were interrogated by law enforcement officials and forced to testify before a grand jury. Ninety-two-year-old Willie Bright was so frightened of “the law” that he wouldn’t even admit he’d voted.

In January 1985, Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, the 39-year-old US Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, charged Turner, his wife Evelyn and Hogue with 29 counts of mail fraud, altering absentee ballots and conspiracy to vote more than once. They faced over one hundred years in jail on criminal charges and felony statutes under the VRA – provisions of the law that had scarcely been used to prosecute the white officials who had disenfranchised blacks for so many years. The Turners and Hogue became known as the Marion Three. (This story is best told in Lani Guinier’s book Lift Every Voice.)

The trial was held in Selma, of all places. The jury of seven blacks and five whites deliberated for less than three hours before returning a not guilty verdict on all counts.

The fact that Sessions would not have seen this as a “racial case” or a “civil rights issue” illuminates a mindset that extends to this day. In recent years, when the Supreme Court dismantled a key enforcement mechanism of the Voting Rights Act, Sessions insisted that “the justification no longer exists” for an enforcement formula that puts an extra burden on states with a history of voting discrimination that wish to change their voting laws.

During the Obama administration, conservatives have railed against the Justice Department for recognizing the reality that laws that don’t mention race can still have discriminatory impacts. Sessions’ comments from 1986 show that he is ready to blithely ignore racial discrimination happening before his eyes.